But Wall Street’s mainstream critics still can’t bring themselves to challenge the top executive ‘right’ to reap enormous riches.

By Sam Pizzigati

Great minds have been searching, ever since last fall’s financial sector meltdown, for an antidote to the wildly excessive Wall Street paydays that made that meltdown inevitable. That search, after over a year, still hasn’t generated anything close to meaningful Wall Street pay reform.

And that has to be puzzling many, if not most, average Americans. The problem on Wall Street, after all, doesn’t seem to be all that complicated. Neither does the solution. Wall Streeters did terrible things — they gutted the pensions and savings of millions — because they were rushing to hit massive pay jackpots. To prevent that greedy rushing in the future, we ought to limit those jackpots.

And Congress could do that — by not letting any banker getting bailout dollars make more than the President of the United States. Or by denying government subsidies or tax deductions to firms that pay their top execs over 25 or 50 or 100 times what their workers make. Or by taxing big bonuses at 90 percent.

And Congress could do that — by not letting any banker getting bailout dollars make more than the President of the United States. Or by denying government subsidies or tax deductions to firms that pay their top execs over 25 or 50 or 100 times what their workers make. Or by taxing big bonuses at 90 percent.

Various bills that take these approaches have actually been sitting in Congress, all this year. Why aren’t these bills going anywhere? America’s big banks, predictably enough, oppose them. But so do many of Wall Street’s mainstream critics. Both these camps have been bending over backwards to steer Congress away from the notion that rewards on Wall Street need serious downsizing.

The banks, by and large, simply deny that these rewards have had any significant impact on how the movers and shakers of high finance behave. In the end, they argue, “the market” will always punish power suits who take reckless risks — and the power-suits know it.

And if those power-suits didn’t know it before last year’s financial meltdown, the apologists continue, they know it now, thanks to last year’s nosedives at Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers.

These nosedives left top execs at Bear Stearns and Lehman holding millions of shares of worthless stock. The Lehman collapse wiped nearly a billion dollars — $931 million, to be exact — off the personal net worth of Lehman CEO Richard Fuld. Bear Stearns CEO James Cayne saw the total value of his personal stock holdings drop by $900 million.

In effect, apologists for Wall Street’s compensation status quo argue, the market system worked. The truly reckless paid a price for their recklessness. So leave that system alone.

Wall Street’s mainstream critics don’t want to leave that system alone. They believe “the market,” left to its own devices, does not adequately discipline the reckless. We need reforms, they believe, that tie executive rewards to “performance” that boosts “long-term shareholder value.”

With such reforms in place, their argument goes, Wall Streeters would have no incentive to take reckless risks — and lawmakers would have no reason to mess with capping the rewards that go to Wall Streeters.

Last week, the most eminent among Wall Street’s mainstream critics — Harvard Law’s Lucian Bebchuk — released a report that takes on Wall Street’s hardline defenders and their claim that the reckless, thanks to the market, have truly suffered for their sins.

This new report powerfully demolishes that hardline claim. But the report, read closely, may just as powerfully undermine the mainstream case against caps.

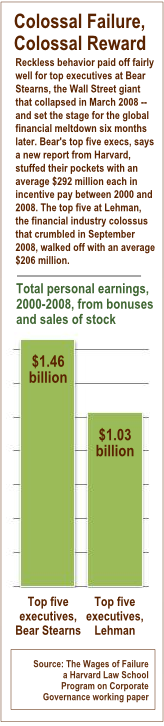

Bebchuk’s new paper revolves around what really happened, on the executive pay front, at Bear Stearns and Lehman. Top execs at these two banks, Bebchuk and his two Harvard co-authors show, did not lose their shirts when the banks crashed. In fact, the top execs at both Bear and Lehman left the crash scene in fine financial fiddle. Spectacularly fine fiddle.

Between 2000 and 2008, the top five executives at Bear Stearns and the top five execs at Lehman together pocketed just under $2.5 billion. About half a billion of that came from annual cash bonuses. They picked up the rest selling off the shares of bank stock they had received as “performance” incentives.

But what about those $900 million “losses” that the CEOs of Bear Stearns and Lehman suffered? Those losses existed only on paper. They represented the difference between the pre- and post-crash value of the Bear and Lehman stock the two CEOs had left in their portfolios when their banks tumbled over the cliff.

In real cash, the two CEOs — despite their epic failures — came out way ahead. For his labors between 2000 and 2008, CEO Cayne of Bear Stearns ended up $388 million to the richer. CEO Fuld of Lehman walked away with $541 million.

So what do mainstream reformers propose, to prevent a repeat of the Bear Stearns and Lehman fiascos? These mainstreamers want execs to get more of their “incentive” pay in stock and less in bonus cash — and have to wait a number of years before they can cash out their stock incentive awards.

If these executives took more pay in stock, the mainstreamers hold, they and their shareholders would share the same self-interest. So “aligned” with shareholders, the executives wouldn’t do anything to jeopardize “long-term shareholder value.” We would all be safe from recklessness.

But these reforms, New York Times analyst Louise Strong points out, had already been put in place at Bear and Lehman — before the two firms crashed.

“Both firms required executives to wait several years before selling their stock,” her report on Bebchuk’s new paper notes. “Both firms paid heavily in stock.”

These requirements, in practical terms, did nothing to discourage short-term recklessness, mainly because Bear Stearns and Lehman awarded massive stock incentives to their executives year in and year out.

Execs at Bear and Lehman did have to wait five years before they could cash out the stock incentives they received in any one year. But after their first five years on the job, they ended up with stock awards they could cash out every year. That gave them plenty of incentive to play risky games that could recklessly jack up their short-term share price.

Bebchuk, in his new paper, acknowledges as much. Having executives wait five years before they cash out, he notes, isn’t go to stop long-serving executives “from placing a significant weight on short-term prices.”

A better approach, Bebchuk suggests, might be the Goldman Sachs policy that requires executives to hold 75 percent of the incentive stock they receive until they retire. But Goldman Sachs execs get the bulk of their windfalls from annual cash bonuses, not stock awards, and annual cash bonuses give execs just as much incentive to think short-term as annual stock awards.

That’s why bolder mainstreamers — like Bebchuk — also want firms to be able to “claw back” bonus awards based on short-term gains that later evaporate.

But clawbacks have their limitations. You can easily, for instance, claw back a single year’s bonus based on a specific accounting fraud. But you can’t so easily claw back the long-term damage that a greedy rush for quick profits — and big bonuses — can do to innocent bystanders.

And top executives can do this damage while appearing to enhance “long-term shareholder value.” The execs at Bear Stearns and Lehman did just that. Year after year, for the better part of a decade, they enhanced shareholder value. Between 2000 and 2007, they quadrupled their bank share prices.

The bottom line: We need more protection from Wall Street greed than the “long-term shareholder value” reform standard can provide us. Americans on Main Street understand that. Why can’t Wall Street’s mainstream reformers?

Sam Pizzigati edits Too Much, the online weekly on excess and inequality.

Discussion

No comments for “Wall Street's Favorite Meltdown Myth Bites the Dust”